As we all know, a lot has changed in six short weeks in our daily lives, in our communities, & in the world. Businesses, schools, workplaces, & public spaces have closed. Mobility & social contact have been limited. Toilet paper & flour are hard to find. We wear masks in public. Grocery store runs are now events. Some of us are now working from our couches, next to spouses & roommates, with kids on our laps & cats traipsing across the trackpads of our computers. Others are still out in the world, yet working under increasingly risky conditions with added protocols & responsibilities. Many aren’t working at all. Loved ones, jobs, & a sense of routine and certainty have been lost.

As a coach & leadership development consultant, my role, under normal circumstances, is to support people in navigating change & transition in their personal and professional lives. One thing I’ve noticed in my work over the years is how often people don’t understand how change works. This makes sense – how many of us ever took a course on “understanding change” in high school or college? I know I didn’t.

Thus, a lot of us have expectations for what we think we should experience that are wildly out of sync with the nature of change. When reality doesn’t align with our expectations, we feel disappointment, anxiety & powerlessness. Many of us then turn inward & shame ourselves for not navigating change “well enough,” adding additional emotional stress to our already overloaded systems.

Change is a naturally stressful experience that involves some level of discomfort. You can’t avoid this. However, you can take time to understand how change works and to reset your expectations for what you might experience physically, emotionally, & tactically during a period of change. And you can extend compassion to yourself and others as we all work through this moment of massive personal and social transition.

Here are four important things to know about how change works:

#1: Change is different from transition.

Change happens in an instant. A decision is made. An order is given. And things are different.

Transition is what happens after something changes. It’s the process we go through and the period of time it takes to metabolize & make meaning of a change. It involves getting our bearings, grieving our losses, adjusting our expectations, creating new routines & structures, figuring out our bigger picture strategy, and understanding the implications of what has shifted in our lives.

Transition takes longer than change. Whereas we can often track changes in our lives in discrete & linear ways – “First, I stopped going into the office & started working from home. Then, I began to have my groceries delivered. Then, my kids’ school closed and they were home all day.” – we can’t do that with transition. On Monday, you might feel like you’ve got a routine in place for yourself to navigate the demands of working with your kids at home. On Tuesday, you might wake up and realize that routine isn’t working at all, and you’ve got to go back to the drawing board. At breakfast, you may feel like quarantine is an opportunity for personal growth, but by lunch, you may be in tears over the reality of all we’ve lost, and by dinner you may have refocused yourself on what’s in your control & what isn’t and found a sense of equilibrium again.

This is the experience of transition: it has ups & downs, moments of clarity & untetheredness.

And this makes sense – while change is about upheaval, transition is about settling in.

I’m a geology lover from Hawai’i, so I imagine change & transition like the process of a volcano erupting. A rift opens up in the earth & spews forth lava in an instant – change. And then it takes time for the ash to settle, the lava to cool into new land, & the plants to regrow – transition.

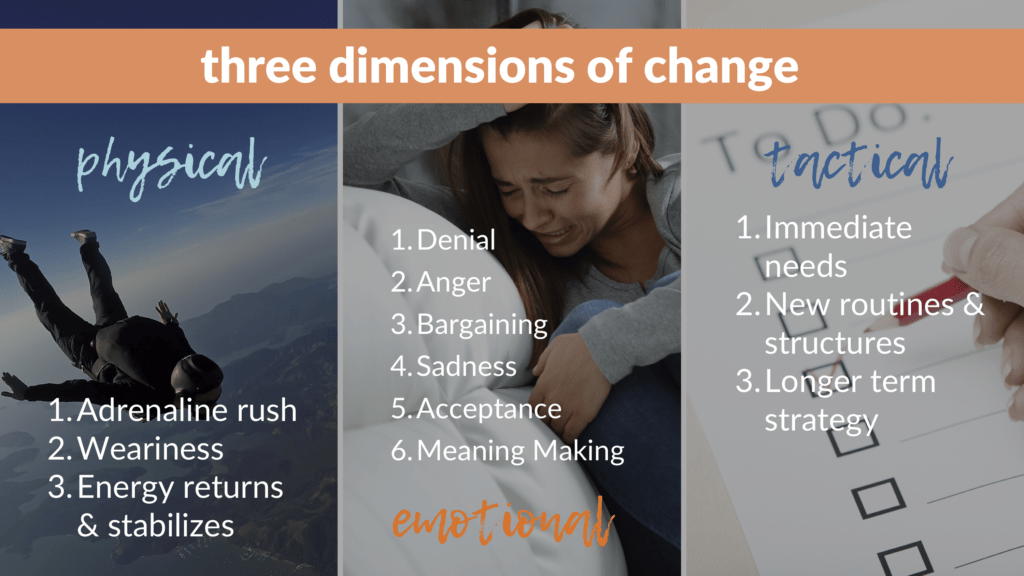

#2: Change impacts us on a physical, tactical, & emotional level.

On a physical level, change spikes our adrenaline, triggering a sense of danger in our brains and flooding our system with chemicals designed to “get us moving fast.” This causes us to work in crisis mode, to solve immediate problems and to focus on meeting our basic needs. Consider how so many of us raced to the supermarket to buy pantry items & toilet paper after shelter in place was initially announced. While we can work off of adrenaline for several weeks, we can’t work off of it forever. Eventually, our adrenaline supply runs out, after which a sense of weariness ensues, as we finally feel the physical impact of all the energy we’ve put out. I’m thinking of how “Zoomed out” I was last week and how all I wanted to do this weekend was sleep. This energy dip is normal – and it doesn’t last forever. If we give ourselves permission to rest, over time our energy returns. Our body & brain chemistry normalize again. We move out of fight, flight & freeze mode and start to be able to think & act more clearly and sustainably.

Change not only impacts us physically, it creates new logistical challenges. Thus, we experience change on a tactical level, as well. Think broadly – coronavirus has presented us with a wealth of logistical challenges that need to be solved at global scale: How do we stop coronavirus from spreading? How do we ensure our hospital systems are not overwhelmed? How do we take care of our most vulnerable populations? How do we develop antibody tests & vaccines? How do we keep the economy going? And the list goes on.

As we work to solve these large scale challenges, each of us is also tasked with generating tactical solutions to smaller personal challenges. Think of all of the logistics you’ve had to handle in the last several weeks. Perhaps your workplace closed and you had to learn how to work virtually, find a new job, or apply for a loan. Perhaps you have children and are now figuring out how to homeschool your kids. At the very least, you’ve likely had to shift how you approach being in community with those you love and how you secure basic items like groceries.

When a change happens, we tend to work in crisis mode first in order to get our basic needs met. In the early days of a change, we focus on solving the most proximate challenges, not on developing long term strategic solutions. We buy toilet paper and stock our freezers – we don’t devise a long term plan to secure the health & well being of our food supply chain or our farmer workers. We secure ventilators & set up emergency medical stations – we don’t immediately develop an antibody test.

As time passes, and we get a handle on our basic needs, our field of vision increases and we begin to be able to think & plan farther out. We start building new routines and structures based on what we are learning about our new context. When my fiance began working from home, he initially kept to his normal schedule: up at 6:30am to work out, done with his day at 6pm. However, without a commute, he essentially added 3-4 hours of work/screen time to his day. Two weeks in, he was exhausted and thus threw his schedule out the window completely. He slept in until he woke up, did work until he ran out of steam, and often skipped his workout. This proved unsustainable as well. Now, five weeks in, my fiance has created a new schedule for himself based on what he’s learned about this new context – he’s up at 8am, works out, has his coffee, gets started by 9:30am, takes a midday break for lunch, works until 5pm and then shuts his computer down. He reports feeling like he’s finally “getting into a rhythm” with his work. He’s creating new routines that help him feel grounded and stabilized through this change. Many of us are – we’re figuring out how to structure our children’s days, when to go to the grocery store, how to exercise, how much screen time we can bear.

This is how change plays out on a tactical level – our field of vision continues to widen, our ability to see and plan for bigger and longer term challenges increases, we become increasingly strategic and creative. And this makes sense – as our physical bodies stop running on adrenaline and our brain chemistry stabilizes, we move out of fight, flight and freeze mode and become more able to make decisions from the rational and higher order parts of our brains.

In addition to impacting us on a physical & tactical level, change also plays out on an emotional one. Change always brings loss with it. Sometimes that loss is very visible – the loss of a job, a relationship, or a loved one. Sometimes it’s less so – the loss of a familiar experience or routine like commuting, the loss of a feeling or state like stability, security or freedom, the loss of a belief in someone or something. Even changes that we perceive as being in our individual and collective best interest carry loss. Think of a job you might have left in the past for one you wanted more. You might say this was a “positive change.” And, in changing jobs, you still lost things (even as you gained things) – you lost an old routine, potentially relationships of familiarity, a sense of knowing what to expect each day.

Wherever loss occurs, grief follows. When we grieve, we process and come to terms with our losses by experiencing a combination of denial, anger, bargaining, sadness, acceptance and sense of meaning. Grief varies in intensity, length, and experience from person to person and situation to situation and is a form of transition, with states that intertwine and double back on each other.

I spent most of yesterday feeling depressed about everything from my friends losing jobs, to the future of my business, to the homeless encampment that’s growing outside my window (sadness). By the end of the day I’d convinced myself “I’m sure everything will work out” (a little denial here). This morning I woke up thinking about how I could self author my experience through this challenging time (meaning making). By lunch I was making plans to do more community outreach because “Maybe if I just do more, I’ll feel better and this will all get better” (bargaining). Who knows where I’ll be by dinner time. When I step back and look in on myself, I see that this “all over the placeness” I’m feeling is me grieving – processing the emotional experience of change.

In the past month, we have lost a lot, not just as individuals, but as a collective.

Some of our losses are obvious – we’ve lost jobs, money, commutes, social interaction, loved ones, routines. Some may be less visible, but no less powerful – a sense of stability, connection, predictability, space from our children & partners, trust in our government, to name a few. We are all grieving, whether we want to admit that or not…and that grieving is happening all at once on an individual, community, and global level. That’s a lot of grief to hold.

Also consider that of all the levels at which change affects us, we are most conditioned to turn away from & dismiss the emotional experience of change. We live in a country where logic is often valued more than emotions, where many of us have been socialized to ignore & repress our feelings and haven’t developed the awareness, vocabulary & set of tools necessary to turn towards & work through the magnitude of loss & grief we are currently experiencing.

I was on a call with a leader the other day who recently let go of half of her staff. I asked how she and her team were making space to process the loss. Without hesitation this leader immediately responded, “We aren’t. Everyone is fine. We just need to believe we did what we needed to, stay positive and move on. There’s work to do.” No judgment of this leader in any way; she is a byproduct of the world in which we live, encouraged to project & to operate as though she and others don’t feel or don’t need to feel. Yet the truth is that we all do feel and that we need time & space to emotionally metabolize our losses, and that there will be significant consequences in the form of depression, burnout, inhumane action, loss of faith & trust if we don’t give ourselves permission to feel and to grieve.

I often find myself wanting to skip to the “end” of the grief cycle – to that future state I hope will arrive sooner rather than later when I feel acceptance around all that’s happened and am able to find meaning in this upheaval. But I realize that it doesn’t work that way – I can’t get to a place of genuine acceptance and meaning without allowing myself the space to feel the loss, the anger, frustration, hurt and sadness that goes along with this change. So I just have to give myself permission to be where I am, and to experience where I’m at with as much compassion and non-judgment as I can.

Notice how we transition through various states on a physical, tactical, & emotional level as time passes. Sometimes we are in one state physically, another emotionally, and another tactically. This is part of what makes the experience of change so complex. I might be in a state of physical weariness, yet feeling deeply angry while trying to make a long term plan for how my organization is going to operate.

As I mentioned before, transition isn’t linear or prescriptive. While the states I shared above may sound discrete & bounded, the experience of them tends to be far more interconnected. Adrenaline spikes, weariness, grief, moments of emerging clarity & groundedness intertwine and often double back on each other. They are expressed and experienced in different ways at different times, for varying lengths of time, for different people.

#3: Over & underfunctioning are normal responses to change.

Change, especially one of coronavirus magnitude, spikes our adrenaline & cortisol levels. Adrenaline & cortisol causes the parts of our brain where rational & strategic decision making occurs literally shut down. We begin making decisions from our limbic brain or emotional center, which causes us to go into fight, flight or freeze mode. Depending on our tendencies, we might start over or under functioning.

Overfunctioners tend to be people with a “fight” tendency – this is me. When change happens, I tend to overfunction – I get busy doing a lot of stuff, making lists, delegating, directing, essentially trying to control anything I can in order to maintain some sense of normalcy or control as the world shifts around me. I’ll be honest, I was one of the people who did personal & community grocery runs, made masks, wrote a bunch of articles on how to work remotely, called all my friends, & ordered an indoor herb garden – all within a week of the initial shelter in place order.

While overfunctioners tend to do more, underfunctioners tend to do less because their default stress reaction tends towards “freezing or fleeing.” A dear friend shared with me the other day that her instinctual response over the last couple of weeks had been to “turtle.” “I’ve stayed inside, binge watched Netflix, & avoided talking to people. I feel so overwhelmed and like if I keep my head down it’ll all go away.” My friend’s way of maintaining a sense of control amidst the chaos was to withdraw rather than engage and to hope that the situation would resolve itself.

It’s easy to judge our responses to change and even to stack rank them against each other. I shared the example above of my friend’s and my response with a colleague the other day who responded “Well, at least you did something.” While we often judge & rank our stress responses, this isn’t generally helpful and it hides the reality of stress responses: that there are pros & cons to each. Yes, overfunctioning enabled me to do a lot; it also led to burn out after a week. Yes, my friend has more energy than I do for the long haul now, and she’s also spent the last several weeks feeling alone & isolated.

In the end, over and underfunctioning aren’t good or bad; they are just normal responses to change designed to help us cope with upheaval.

At the same time, normal doesn’t mean “perpetually necessary.” By knowing what your tendency is, you can learn to spot it in action and to recognize when it’s helpful and harmful to you. In reflecting on my own response a couple weeks ago, I think it was helpful that I took action to take care of my basic needs and to reach out and support others in doing the same. Did I need to do that to the extent that I did, at the pace I did, & exhaust myself in the process? Probably not…and I can now be more aware of that in the future.

#4: We can work with or against change.

While we can’t avoid change and the natural discomfort that goes along with it, we can certainly do things that intensify how hard the emotional experience feels and how difficult the practical experience is to navigate. Here are some common ways we make change harder:

- Holding unrealistic expectations for self & others (especially around pace, perfection, & productivity)

- Not giving ourselves permission or space to feel & grieve losses

- Blaming or shaming ourselves for not “having it all figured out yet”

- Trying to control things we can’t control

- Burning the candle at both ends and not prioritizing self care

- Expecting everyone to be on the same physical or emotional timeline for processing change

- Competing with yourself or others to “do change” better or the best

We can also do things that make it easier for us to navigate change. These things tend to increase our sense of efficacy & creativity and lighten (or at the very least, not increase) the emotional load we carry. Here are some common ways we can work with change:

- Setting reasonable expectations for what’s possible for ourselves & others during times of change

- Making space to check in with ourselves about how we are feeling physically & emotionally

- Giving ourselves permission to feel, to feel wildly different from moment to moment, & to grieve what we’ve lost

- Monitoring our energy gas taking & prioritizing self care so we aren’t running on fumes

- Getting clear about what matters more or less at a moment in time and prioritizing what’s most important

- Focusing on what’s in our locus of control

- Finding our way forward by “trying on” microchanges to our routines & actions, observing what happens, then adjusting (rather than forcing ourselves to have answers before we do anything)

- Leaning into our community and being willing to ask for & receive support

We are in a time of transition – as individuals & as a global community.

We are grieving and grappling and figuring it out on every level – personally & professionally, as families & friends, as local communities, as nations, & as a world.

I find that people, myself included, often want to skip transition. We want to jump from the routine of one way of operating into the routine of a different way of operating without experiencing the messiness that exists in between. We want to go from a place of “I’ve got it figured it out” to “I’ve got it figured out” without experiencing “I have no idea how to figure it out” and “I’m in the process of figuring it out.”

I get it. I really do. More than once I day I find myself wishing I was more resourced, resolved, & routinized around a whole host of things. And the truth is…I’m not. We are not.

If you’re feeling a sense of unthetheredness right now, you aren’t alone, and you aren’t making it up. We are untethered right now. We will likely be that way for awhile. And consider that this feeling of untetheredness is not necessarily an indicator that you as an individual or we as a society are “in the wrong.” This is simply what transition feels like. It’s part of the nature of change.

We can’t skip over it. We have to find our way through it.

And how we navigate this transition in part depends on our willingness to acknowledge & accept where we are without shame or judgment.

Beating up on yourself or others for being in transition does not help you or us move through it any faster. It only adds layers of shame to your and our already full emotional plate and makes the process of metabolizing our losses, integrating our learnings, & creating the future harder.

So my invitation to you is to take a moment to view your experience of now through the lens of transition and to locate yourself. Where are you physical, emotionally, & tactically in this period of change? While understanding where you are won’t “change” or “fix” it, hopefully it will help you see that whatever you’re feeling is not a “you failing” but a byproduct of change. And, hopefully it will help you navigate this moment in time with more awareness, perspective, & compassion.

Want to learn more about how change works and how to strengthen your ability to work through change and transition? Check out Find My Way Forward, my latest online course.